Climate Emergency

Comments

-

An interesting episode of the Rest is Politics with the chair of the government's Climate Change Committee. A very knowledgeable and eloquent speaker.

https://youtu.be/2osysX_tYe0?si=V8igne6qELIDllxW

https://youtu.be/2osysX_tYe0?si=V8igne6qELIDllxW

0 -

Rare earth and man made radioactive sludge.

Perhaps there’s another way?

0 -

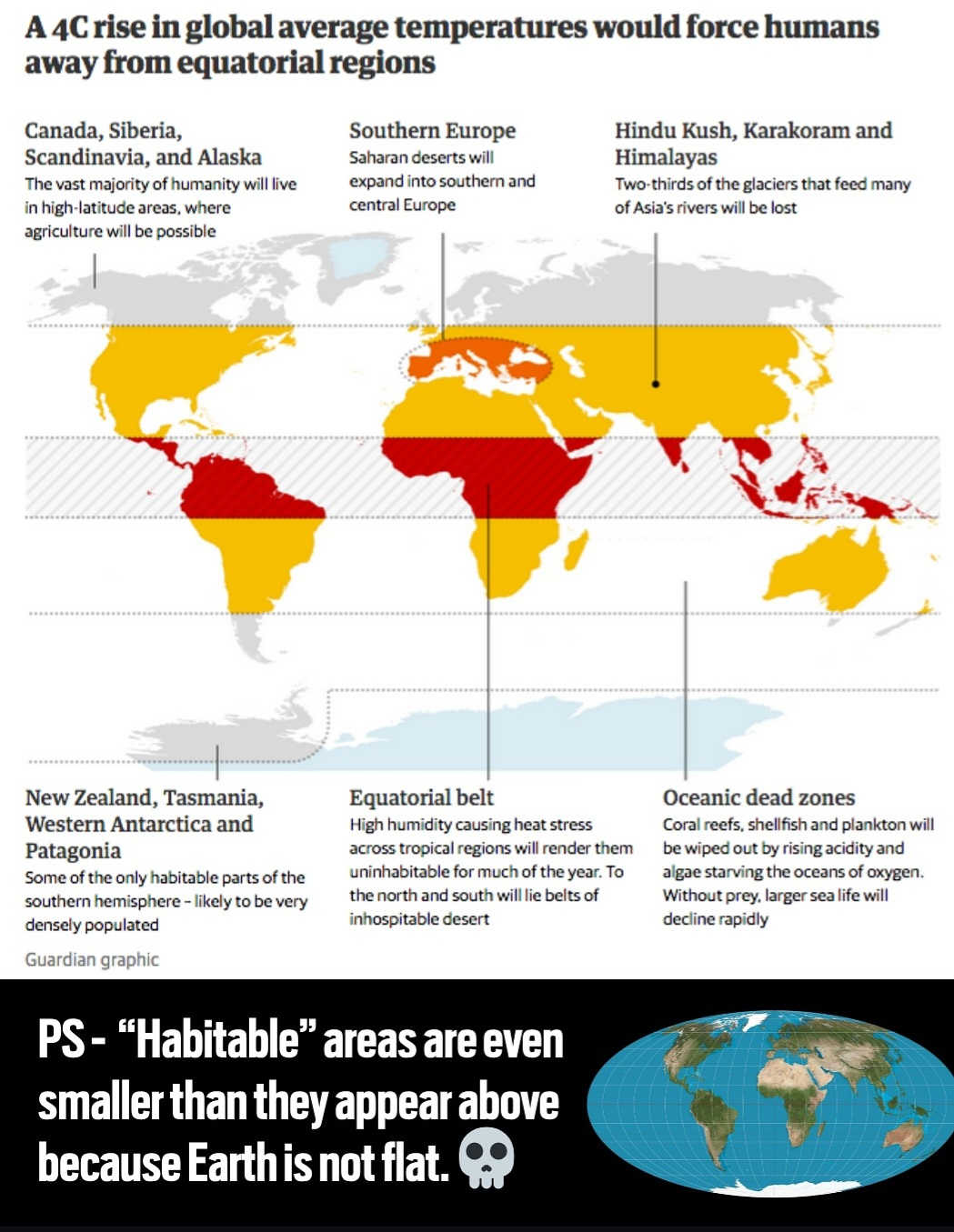

Thanks for postingcantersaddick said:A recent study of studies (a study that pulls together all the peer reviewed evidence on a topic over a period of over a decade to find a most likely case or average result of the findings and is itself peer reviewed as a paper) has been published on climate change. It should be big news but the coverage has been limited.

Below is a few exerpts of bits of commentary/summaries of it. Worrying stuff.

0

0 -

There is. The technology has developed hugely and will continue to do so. Solid state batteries which are now being produced in China require a tiny tiny percentage of the minerals a standard lithium ion battery does and are massively more efficient at storage. And with the potential to be hundres of thousands of times more efficient, BYD are saying they think in a couple of years they will be able to produce a battery the size of a football that can power a house for a month.MrWalker said:Rare earth and man made radioactive sludge.

Perhaps there’s another way?

The issues with batteries have only every focused on lithium ion batteries which have only ever been a temporary solution, a stepping stone as better technology develops. Whilst I'm not writing off the issues here (part of which are clearly down to not having the regulations on how to ethically mine and despose of the material) articles like this are focusing on a temporary problem. And as demand for electric tech grows this drives investment in new tech and so the tech gets better. Which is why governments setting targets for electric vehicles and stimulating demand with incentives while the tech isn't quite perfect is still the right thing to do. As it speeds up the development of new tech and improved tech.4 -

A sign of things to come

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx2073zy4k9oNationally, England recorded its warmest June on record after the driest spring for 132 years.

According to Yorkshire Water, reservoir levels currently stand at just over 50% - a record low for the time of the year and "significantly below" the average for early July, which is nearer 80%.

0 -

Sorry, who's BYD?cantersaddick said:

There is. The technology has developed hugely and will continue to do so. Solid state batteries which are now being produced in China require a tiny tiny percentage of the minerals a standard lithium ion battery does and are massively more efficient at storage. And with the potential to be hundres of thousands of times more efficient, BYD are saying they think in a couple of years they will be able to produce a battery the size of a football that can power a house for a month.MrWalker said:Rare earth and man made radioactive sludge.

Perhaps there’s another way?

The issues with batteries have only every focused on lithium ion batteries which have only ever been a temporary solution, a stepping stone as better technology develops. Whilst I'm not writing off the issues here (part of which are clearly down to not having the regulations on how to ethically mine and despose of the material) articles like this are focusing on a temporary problem. And as demand for electric tech grows this drives investment in new tech and so the tech gets better. Which is why governments setting targets for electric vehicles and stimulating demand with incentives while the tech isn't quite perfect is still the right thing to do. As it speeds up the development of new tech and improved tech.

0 -

Chinese electric car company (plenty of them on the roads in the UK once you spot one you keep spotting them). Widely thought of as top of the range tech wise for EVs now and ahead of Tesla. They have been investing heavily in battery tech for a while as they know cracking that will make them market leaders in EV sales. They have got the first solid state batteries out in China. Not yet quite right for cars but suitable for home solar/small scale off grid stuff. Needs a bit of adapting for cars and to get full potential from the tech.Stig said:

Sorry, who's BYD?cantersaddick said:

There is. The technology has developed hugely and will continue to do so. Solid state batteries which are now being produced in China require a tiny tiny percentage of the minerals a standard lithium ion battery does and are massively more efficient at storage. And with the potential to be hundres of thousands of times more efficient, BYD are saying they think in a couple of years they will be able to produce a battery the size of a football that can power a house for a month.MrWalker said:Rare earth and man made radioactive sludge.

Perhaps there’s another way?

The issues with batteries have only every focused on lithium ion batteries which have only ever been a temporary solution, a stepping stone as better technology develops. Whilst I'm not writing off the issues here (part of which are clearly down to not having the regulations on how to ethically mine and despose of the material) articles like this are focusing on a temporary problem. And as demand for electric tech grows this drives investment in new tech and so the tech gets better. Which is why governments setting targets for electric vehicles and stimulating demand with incentives while the tech isn't quite perfect is still the right thing to do. As it speeds up the development of new tech and improved tech.1 -

Thanks for bringing that sense of perspective on batteries, Canters. It does change the discussion quite a bit.1

-

A New York Times Article - 09/07/25

The world can have non-Chinese rare earths — for a price

Here’s what I thought I knew about rare earths: One, they’re important. (They’re in our smartphones! We can’t live without smartphones!) Two, they’re rare. Three, they come mostly from China, which mines and processes them in ways that are both dirty and ethically problematic.

They’re certainly important: They’re needed not just in phones but in cars, semiconductors, medical imaging chemicals, robots, offshore wind turbines and a wide range of military hardware.

But it turns out they’re not all that rare: They can be found all over the world. They’re just very spread out and hard to refine.

And as it happens, the world doesn’t have to depend on China for them either. As I learned from reading two stories about rare earths by my colleagues this past week — one from China and one from France — relying on China for these strategically important resources was a choice: For Western countries, it outsourced pollution; for everyone, it kept production costs down.

But rare earths could be produced differently. They could be cleaner. They could come from non-Chinese sources. All of this, however, has a price tag attached.

Baotou vs. La Rochelle

This year, my colleague Keith Bradsher traveled to Baotou, a flat, industrial city of two million people in the Inner Mongolia region of China that calls itself the world capital of the rare earth industry. While the air in Baotou no longer has the acrid, faintly metallic taste that he found during a 2010 visit, a huge lake of toxic and radioactive waste has not been cleaned up. He also traveled to Longnan, in south-central China, another town that produces rare earths. There, he found a creek in front of some mines that was, as he put it, “bright orange and bubbling mysteriously.”

Contrast these scenes with the warehouse my colleague Jeanna Smialek visitedin La Rochelle, a picturesque port city that has long ranked among the most livable places in France. A new rare-earths production line there takes recycled materials and, using “giant metal tanks topped by gently whirring motors,” distills out two key minerals used in magnets. (Fun fact: Rare earth magnets can be 15 times as powerful as iron magnets of the same weight.)

The catch? It costs about 20 percent more than importing the rare earths directly from China.

Longnan, a Chinese rare earths production hub. Keith Bradsher for The New York Times Lower cost, higher risk

Importing cheap Chinese rare earths comes with big risks. In April, in response to President Trump’s tariffs, China temporarily suspended almost all exports of seven kinds of rare-earth metals, as well as some of the very powerful magnets made from them.

The resulting shortages at car plants in the U.S. and Europe — a Ford Explorer factory in Chicago had to close temporarily — brought home the real cost of outsourcing these strategic minerals.

So the question is: Are countries prepared to shell out more, not just for cleaner rare earths, but also for their own strategic independence?

It’s not clear that the answer is yes. Europe has, for example, long relied on cheap Russian gas and avoided investing in military deterrence. And even though China first cut off rare earth supplies to Japan in 2010, few countries have since taken meaningful steps to diversify.

But reading these two pieces together, it’s hard not to be struck by the stark contrast between two different versions of the same industry. Rare earth production can be relatively clean. It doesn’t have to be the near-exclusive domain of a country that weaponizes its industry dominance. But this sort of rare earth would be more expensive. Is anyone willing to pay?

0 -

Without quoting the whole post. that last sentence is the key point but as I said above as the tech develops to require less of these materials then it becomes more economically viable to get them from cleaner sources.0

-

Sponsored links:

-

4 -

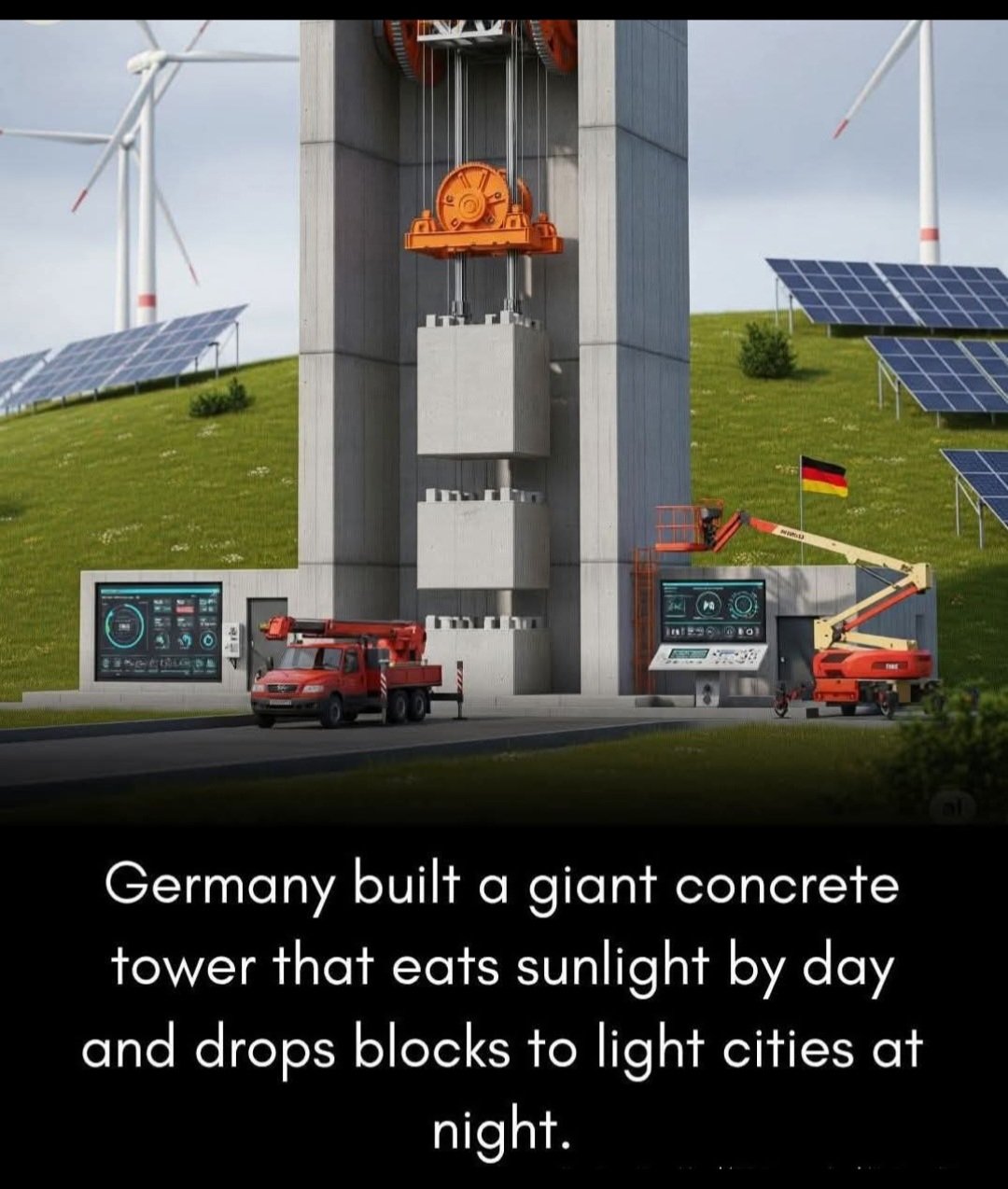

Damn. This technology is so cool!

Also this:

8 -

More cool tech

More cool tech

2 -

That's AI generated. It's an interesting area of research, and there *are* prototypes, but they're nowhere near ready for mass production and deployment.cantersaddick said: More cool tech

More cool tech

0 -

I would imagine weeds and other river debris might prove an issue. Perhaps less so in Norway but our rivers might not be ideal for it.0

-

It would be a shitty idea in our riversShootersHillGuru said:I would imagine weeds and other river debris might prove an issue. Perhaps less so in Norway but our rivers might not be ideal for it.1 -

Bit late to this. I know thebpic is obviously AI but I thought the project actually existed no?Leroy Ambrose said:

That's AI generated. It's an interesting area of research, and there *are* prototypes, but they're nowhere near ready for mass production and deployment.cantersaddick said: More cool tech

More cool tech

On further inspection maybe not. There were a series of articles about it that seem to have been taken down. Reading the fact checks about it, the tech does exist and is used for tidal power including in Scotland. But Norway haven't actually implemented in rivers (though there are proposals to do so).

This company does exist and the tech looks cool too.

5 -

More on the benefits of deleting storage.

Source BBC, today

“Can deleting old emails help save water?Simran Sohal

BBC Verify researcherWith parts of the UK experiencing their fourth heatwave of the summer and millions subject to hosepipe bans, the National Drought Group has called the current water shortfall a "nationally significant incident.", external

The group, which includes the Environmental Agency, Met Office and water firms, has suggested deleting old emails and photos as one way to save water at home.

The group says data centres “require vast amounts of water to cool their systems.", external

This has attracted quite a bit of attention online, so let’s dig into the data.

According to a Thames Water estimate, external, a large data centre might use anywhere from four to 19 million litres of water per day to cool their servers - the same as supplying the daily demand of more than 50,000 households.

However, water for cooling servers accounts for just 25% of the total amount of water consumed by data centres in the UK, the Environment Agency say.

The rest is used to generate the electricity these centres need to store data in the first place.

Overall, the agency told BBC Verify that deleting 1,000 emails with attachments would save approximately 77.5 litres of water per year.

These are all estimates, however, and are subject to lots of variation, including the size of emails and pictures

The UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has told BBC Verify that emails and photos are small files and “would not significantly reduce water consumption”.

It says that the focus should be on how building more data centres may contribute to water scarcity. That’s a concern not just in the UK, but across the globe.

According to the International Energy Agency, external, data centres, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence consumed almost 2% of global electricity demand in 2022, roughly equivalent to the consumption of Japan.

By 2026 that demand could double, the agency say, putting more pressure on global water supplies than ever before.

0 -

Don't the people who research this sort of stuff have something better to do? The battle is lost, and has been for sometime I fear. I will, of course, now have to spend vast amounts of time sorting through what I need to keep, not much I guess, now that I'm better educated on the subject, so thanks a bunch for posting it 😉 I seriously doubt many will bother though. Ke Sera!MrWalker said:More on the benefits of deleting storage.

Source BBC, today

“Can deleting old emails help save water?Simran Sohal

BBC Verify researcherWith parts of the UK experiencing their fourth heatwave of the summer and millions subject to hosepipe bans, the National Drought Group has called the current water shortfall a "nationally significant incident.", external

The group, which includes the Environmental Agency, Met Office and water firms, has suggested deleting old emails and photos as one way to save water at home.

The group says data centres “require vast amounts of water to cool their systems.", external

This has attracted quite a bit of attention online, so let’s dig into the data.

According to a Thames Water estimate, external, a large data centre might use anywhere from four to 19 million litres of water per day to cool their servers - the same as supplying the daily demand of more than 50,000 households.

However, water for cooling servers accounts for just 25% of the total amount of water consumed by data centres in the UK, the Environment Agency say.

The rest is used to generate the electricity these centres need to store data in the first place.

Overall, the agency told BBC Verify that deleting 1,000 emails with attachments would save approximately 77.5 litres of water per year.

These are all estimates, however, and are subject to lots of variation, including the size of emails and pictures

The UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has told BBC Verify that emails and photos are small files and “would not significantly reduce water consumption”.

It says that the focus should be on how building more data centres may contribute to water scarcity. That’s a concern not just in the UK, but across the globe.

According to the International Energy Agency, external, data centres, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence consumed almost 2% of global electricity demand in 2022, roughly equivalent to the consumption of Japan.

By 2026 that demand could double, the agency say, putting more pressure on global water supplies than ever before.

0 -

Absolute, total, complete, and utter bollocks. That's like saying a child should be prevented from riding their scooter on a playground because it might emit some tyre particulate pollution whilst 500 arctics thunder past on the bypass 100 metres away.MrWalker said:More on the benefits of deleting storage.

Source BBC, today

“Can deleting old emails help save water?Simran Sohal

BBC Verify researcherWith parts of the UK experiencing their fourth heatwave of the summer and millions subject to hosepipe bans, the National Drought Group has called the current water shortfall a "nationally significant incident.", external

The group, which includes the Environmental Agency, Met Office and water firms, has suggested deleting old emails and photos as one way to save water at home.

The group says data centres “require vast amounts of water to cool their systems.", external

This has attracted quite a bit of attention online, so let’s dig into the data.

According to a Thames Water estimate, external, a large data centre might use anywhere from four to 19 million litres of water per day to cool their servers - the same as supplying the daily demand of more than 50,000 households.

However, water for cooling servers accounts for just 25% of the total amount of water consumed by data centres in the UK, the Environment Agency say.

The rest is used to generate the electricity these centres need to store data in the first place.

Overall, the agency told BBC Verify that deleting 1,000 emails with attachments would save approximately 77.5 litres of water per year.

These are all estimates, however, and are subject to lots of variation, including the size of emails and pictures

The UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has told BBC Verify that emails and photos are small files and “would not significantly reduce water consumption”.

It says that the focus should be on how building more data centres may contribute to water scarcity. That’s a concern not just in the UK, but across the globe.

According to the International Energy Agency, external, data centres, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence consumed almost 2% of global electricity demand in 2022, roughly equivalent to the consumption of Japan.

By 2026 that demand could double, the agency say, putting more pressure on global water supplies than ever before.

It's a distraction tactic to get people creating a false equivalence between Joe Bloggs storing photos in the cloud, and companies building data centres to power AI. Pathetic client journalism.6 -

Sponsored links:

-

Meanwhile three billion litres are lost every day through the UK's leaky pipes. Still, keep deleting those emails.3

-

Thing is. It should still be a worthwhile thing to do. Cloud space shouldn't be wasted on stuff not needed/used.

But like you say the comparisons to the massive data centres and corporate level waste is mad.1 -

Think global. Act local.

Could be catchy.1 -

I'm not sure whether I'm being trolled here. This is genuinely like one of those memes about data being physically heavy - and 20 terabytes of it causing rhe floor of a datacenter to collapse. Deleting a fucking photo doesn't magically make the storage disappear, for Christ's sake 🤣🤣🤣cantersaddick said:Thing is. It should still be a worthwhile thing to do. Cloud space shouldn't be wasted on stuff not needed/used.

But like you say the comparisons to the massive data centres and corporate level waste is mad.0 -

BBC verify eh? What are they like?0

-

Taken from The New York Times

Trump wants to kill clean energy abroad

President Trump is not just trying to stop the transition away from fossil fuels in the U.S. He is pressuring other countries to retreat from their climate pledges and burn more coal, gas and oil.

He is doing that by applying tariffs, levies and other mechanisms of the world’s biggest economy, my colleague Lisa Friedman reports from Washington. A White House spokesman said that the administration “will not jeopardize our country’s economic and national security to pursue vague climate goals.”

Here are some of the ways the Trump administration is trying to affect other countries’ climate policies:

- The administration promised to apply tariffs, visa restrictions and port fees to countries that vote for a global agreement to slash greenhouse gas emissions from shipping.

- Virtually all of the administration’s trade deals include requirements that trading partners buy vast amounts of U.S. oil and gas.

- The administration joined oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia to oppose limits on the production of petroleum-based plastics.

Energy experts and European officials called the level of pressure Trump is exerting on other countries worrisome. Scientists widely agree that to avoid worsening consequences of climate change, countries need to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy sources like wind, solar, geothermal power and hydropower.

0 -

The fossil fuel industries are terrified of losing their ability to make billions across the world. They fund parties of a certain political leaning in order to promote oil and gas and put down anyone recognising that man made Climate Change is having a drastic effect on the planet. It's frightening, but money talks and big corporations are doing a lot of talking.ShootersHillGuru said:Taken from The New York TimesTrump wants to kill clean energy abroad

President Trump is not just trying to stop the transition away from fossil fuels in the U.S. He is pressuring other countries to retreat from their climate pledges and burn more coal, gas and oil.

He is doing that by applying tariffs, levies and other mechanisms of the world’s biggest economy, my colleague Lisa Friedman reports from Washington. A White House spokesman said that the administration “will not jeopardize our country’s economic and national security to pursue vague climate goals.”

Here are some of the ways the Trump administration is trying to affect other countries’ climate policies:

- The administration promised to apply tariffs, visa restrictions and port fees to countries that vote for a global agreement to slash greenhouse gas emissions from shipping.

- Virtually all of the administration’s trade deals include requirements that trading partners buy vast amounts of U.S. oil and gas.

- The administration joined oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia to oppose limits on the production of petroleum-based plastics.

Energy experts and European officials called the level of pressure Trump is exerting on other countries worrisome. Scientists widely agree that to avoid worsening consequences of climate change, countries need to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy sources like wind, solar, geothermal power and hydropower.

4 -

Trump is a fucking fossil himself, maybe we should burn him and power Manhattan for a month in doing so?4

-

An impending agreement to make shipping the first industry sector with net zero targets has come under pressure from the US, Saudi and Russia and been deferred in London today. Reported basis of arguments, as ever, "cost to consumers". I fear we will be in a toxic soup before long and still be told it's costs and profits that come first.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c3vnl0yxg53o0 -

Yeah horrendous news. Particularly given all the news this week about the world's coral reefs reaching a key tipping point.0